In this section you will find personal narratives reflecting on my experiences of being on, with (and occasionally), in the sea.

Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes

As Jimmy Buffett sang, “Nothing remains quite the same”. After two years of working a fractional appointment as an Associate Professor at AUT I decided, at short notice, to step aside from my academic career and pursue other interests at the end of 2025. At this point in time, ‘other interests’ is very much concentrated on sailing. I’m writing this from Whangaroa Harbour, Northland as we (co-owner and I) make our way north to round North Cape and head down the west coast of the North Island towards Nelson. From there we want to head further south towards Stewart Island and Fiordland. The plan is to spend 4-5 months cruising, then…..? I’m neither old nor wealthy enough to retire.

Nicole is spending a few weeks with a visiting Canadian auntie and will join us soon. We spent just over a week holed up in the Bay of Islands avoiding easterly gales and rain and then strong westerlies which have battered much of the country.

For me, one of the joys of cruising is going with the flow – if the weather is unfavourable then sit things out; read a book (or two or three). While we have Starlink, the constant news feeds and opinion pieces, relating to what is an increasingly dysfunctional world are disheartening and detract from what is actually a very special time. I’m trying to disconnect from the ‘external world’ over which I have no control; a point well made by Nigel Latta in Lessons on Living (2025). His excellent, unfortunately final book (written when he was terminally ill with cancer), was a birthday gift from friends. As the wind blew and the rain hammered down I had the opportunity to ‘have a conversation’ with Mr Latta, for that is very much the tone of the book. It’s a reflection of a life well lived, but sadly cut short, in which he shares “pocket sized wisdom”. I won’t reveal all, as I’d recommend you get hold of a copy to really appreciate his talent for communicating a wide range of ideas/concepts. As with any form of media (visual, print, video) we interpret/understand what is presented through our own experiences, biases and blind spots. So, bear with me as I very briefly outline his three principles (informed by my nautical setting).

- Drive the boat (well bus actually). Don’t be a passenger in your own life; act with intention. We all experience various situations, good, bad or indifferent. We can’t control these – but we can decide how we will respond. Rather than being driven by emotion-driven responses or biases we should take the opportunity to pause and respond with purpose. I can’t change the weather systems battering the region at present – but I can choose to be frustrated or accept that this is cruising, and these circumstances provide me with time to read, or do some engine/boat maintenance.

- Focus on the things you can control. Don’t waste time and energy on things you can’t control (e.g., frustration with the proposed ‘take over’ of Greenland, or the denigration of allied troops’ contribution in Afghanistan); instead focus on the things you can control (e.g., plans for the next favourable period of weather, rechecking safety gear). A boat is like …. a boat (there is always something to fix). I can attend to the numerous small tasks that keep the boat safe and ready for several months of constant use.

- Teamwork. The best work we ever do is with other people. I’m conscious that a boat is a confined space, and that we all have different preferences, habits (some benign, some annoying), and ways of doing things. It’s important that this is a place where it’s okay to make mistakes, the important thing is to learn and above all have a shared purpose. As Nigel Latta noted, “We learn the most from our failures, not our successes”. Heaven knows how many voyages have ended with ‘awkward’ crew dynamics, or in the case of a certain Capt. Bligh, a long voyage in a small boat.

There is the final section in the book where Nigel discusses how we might measure the success or failure of what we set out to accomplish in life. I’d encourage you to investigate what he has to say.

I am thankful to thoughtful friends for such a fine gift and to Nigel Latta for his honesty, in what was a real battle of life and death. We are enriched by his writing but sadly denied further words of (un)commonsense wisdom.

Our latitudes are changing as we sail the length of New Zealand, it’s my challenge to see if I can match that with appropriate changes in attitude……time will tell.

January 2026

Degrees of Freedom

I wanted freedom, open air, adventure. I found it on the sea.

Alain Gerbault (first French circumnavigator)

I’ve recently read Andrew Fagan’s Swirly World, Lost at sea, where he reflects on his attempt to undertake a solo circumnavigation. On leaving port he writes, “It’s just you and this boat now. No outside controlling authority to command the use of time for remuneration in whatever local currency. This kind of recreational self-determined boating constitutes relative freedom to many. Expensive relative freedom when all the costs for fitting out and provisioning are added up.” As an experienced sailor Fagan acknowledges that the ‘type’ of freedom one might experience isn’t absolute.

The prolific sailor/author John Kretschmer is also conscious of the ‘boundaries’ of our so-called freedom of the sea. He states, “Storms and stories dominate our memories of ocean voyaging, but the freedom starts as soon as you slip the lines and head out to sea. I feel a powerful release for the clutches of land life every time I shove off. I’ve been chasing this freedom my entire life, and for the most part, I’ve been lucky to find it.…This freedom has demands and consequences. You must be willing to embrace a degree of self-reliance that is unnerving to some: there are times you have no one to rely on but yourself and your shipmates – everything depends on you and your resourcefulness.”

In Western popular culture, the concept of freedom of the sea is often romanticised as a symbol of adventure, escape, and personal liberation. Films like Pirates of the Caribbean portray the ocean as a lawless frontier where characters seek autonomy beyond the reach of governments and societal norms. Music, too, reflects this ideal—songs like Come Sail Away (Styx) and Sailing (Christopher Cross) evoke the emotional and spiritual freedom associated with open waters. In literature we find this sentiment expressed in Bernard Moitessier’s famous quote from The Long Way, when he chose not to return to England to claim victory in the Sunday Times Golden Globe race, but instead to continue sailing: “I am continuing non-stop to the Pacific Islands because I am happy at sea, and perhaps also to save my soul”. For Moitessier the sea was not just a physical space but a sanctuary – a place where he could live authentically, free from the pressures of modern society.

However, even a cursory investigation reveals that in Western culture, the concept of freedom of the sea has contentious historical and geopolitical roots. The concept, while rooted in ideals of openness and equality, has also been critiqued as a tool of Western imperialism. A pivotal moment in the codification of this ideal was the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius’ 1609 treatise Mare Liberum (“The Free Sea”). He argued that the sea was international territory and should be free for navigation by all. This allowed European powers like Britain, Spain, and Portugal to use naval force to ensure free passage of their ships to embark on global exploration and colonization. The idea that no one owned the sea allowed Western empires to navigate, conquer, and control distant territories for their economic and strategic advantage. While the recreational sailor today may be unaware of the historical context, the ‘idea’ of freedom of the sea resonates strongly as an escape from the perceived trials and tribulations on land.

So how might we understand the freedom of the sea that is available to us?

Gregory & Tod Bassham have explored the paradoxical nature of freedom in recreational sailing through the lens of Stoic philosophy. Sailing, they argue, offers a profound sense of liberation -casting off from shore becomes a symbolic escape from societal constraints, bureaucracy, and emotional burdens. Yet, this freedom is not absolute. True seamanship requires acknowledging the limits of personal agency and submitting to elemental forces like wind, weather, and tides. Freedom, they argue, lies not in controlling external events, but in mastering one’s response to them. As sailors we must understand what we can control, what can be influenced, and what must simply be accepted: both at sea specifically, and in life more generally. Their writing positions sailing as a metaphor for human existence: a journey where freedom is found not in dominance, rather found in coming to terms with what we can, and cannot, control.

While being nowhere near as philosophical, Mark Orams and I have written about freedom from the perspective of a cruising sailor. These reflections align with Kretschmer’s writing and the Basshams’ acknowledgement of the need to accept what lies beyond our control. We contend that freedom is a circumstance that is filled with uncertainty, risk, and personal responsibility—including bearing the consequences of misfortune, decisions, and actions/inactions that may result in an undesirable outcome. Any life choice, especially those freely chosen, has obligations and responsibilities associated with it. At sea, freedom from one set of (land-based) obligations and pressures is replaced by others: safe navigation, weather, repairs, sickness, and compliance with rules and regulations. While there can be an escape from terrestrial obligations and, therefore, a sense of freedom associated with that, there is a commensurate series of other challenges and issues that must be dealt with.

In short, sailing requires adherence to an alternative set of obligations; one is clearly not free – freedom is relative and freedom at sea is arguably a romantic construct that may be based more on perception than the gritty reality of life aboard a sailing vessel.

The accessibility of services such as Starlink, for those who voyage in previously ‘unreachable’ places, poses both practical and philosophical questions for those who seek some sense of freedom at sea. One is now required to make a deliberate decision to reject constant connectivity and embrace what remains of the (relative) freedom of the sea. Will we find the freedom we are seeking if we unconsciously accept the intrusion of something that we can control?

August 2025

Of Fathers and Sons

I am deeply aware of how my father influenced my love of the sea and boats. This ‘love affair’ may have developed in time of its own accord – but it certainly got a kick start with boating magazines, boat building projects, and sailing from a relatively young age. Thousands of hours dreaming, talking, working, and boating alongside one another added a richness to our relationship that came from a shared passion. I know that there are other passions that draw family members together. I also know that this relationship is not exclusive to fathers and sons – but as a personal blog this is the one that I can write about. I also have a passion for books and below are several that I have on my bookshelf that have resonated because they touch on fathers and sons and the sea. It’s not an exhaustive list, nor a complete synopsis of each book – more a nod to the value of shared interests and the legacy of being in, on, or with the sea alongside one’s father (or son).

Kennedy Warne begins his recent book Soundings with a description of rowing from Russell Beach out to a family boat with his 92-year-old father. He traces his intergenerational connection to this place and the sea as he and his father make the journey south to Auckland. One evening they go fishing in a dinghy that they had built together a few decades earlier and Kennedy describes how this was not the first time they had worked alongside one another to build a boat. The first was a Des Townson Starling sailing dinghy, a class which I also owned and lavished care on by repainting and varnishing under the guidance of my father. Kennedy then tells of working alongside his own son, 50 years later, restoring a Townson keelboat. There is a symmetry in this narrative: father to son, son to grandson…. or in Kennedy’s words, “Like father, like son”.

In a slightly different vein, in My Old Man and the Sea, we gain an insight into the changing relationship between father and son, David and Daniel Hays. The two sail from New London, Connecticut, through the Panama Canal, to Rapanui, around Cape Horn and back to New London on Sparrow, a 25ft Vertue cutter. The account is both an adventure narrative and the exploration of their changing relationship. Told in alternating voices the book explores not only the physical challenges of the sea but also the emotional foundations of their father-son relationship. As a father, David confronts his waning strength and past parenting regrets, while Daniel seeks to establish his independence. Fast forward forty years and David, who is now in his nineties, and Daniel, who is now older than his father was at the time of the voyage (63 cf. 55), have recently gifted Sparrow to a young Canadian couple.

A variation on the filial theme is Paul Heiney’s deeply personal and reflective memoir, that chronicles his sailing journey from the UK to Patagonia, and Cape Horn, in the wake of his son Nicholas’ death. In One Wild Song, Paul reflects on the loss of his son to suicide and while the book is a sailing adventure, it contains an account of dealing with grief and healing. As Heiney navigates treacherous seas and long stretches of solitude, he reflects on Nicholas’ life, his struggles with mental health, and the joy he brought into the world. The voyage becomes a way for a father to process his loss, confront his emotions, and find a sense of peace. It is above all a testament to the enduring bond between a loving father and son.

Not all accounts of the relationship between fathers and sons are positive. Charles Doane’s excellent The Boy Who Fell To Shore chronicles the complex and ultimately tragic ending to Thomas Tangvald’s life. Thomas was the son of Peter Tangvald, who drowned, along with his daughter Carmen, in a shipwreck whilst Thomas survived. At fifteen Thomas found himself orphaned and somewhat adrift. His unconventional upbringing at sea and the death of his mother (killed by pirates), led him into cycles of addiction and unstable relationships. Thomas’ father had seven wives, two who lost their life at sea. While Peter may have been charismatic, he also held strong views – leading one person who encountered him to describe him as a Nazi. Doane describes how Peter constructed a ‘jail cell’ in the forepeak of the boat where he would contain the children. This cabin could be locked from the outside and had a grating on the hatch. So while Thomas learnt much from his father, it is hardly surprising that despite his undoubted intelligence, and seafaring pedigree, he struggled to find peace and stability. Thomas is thought to have lost his life at sea, having failed to return from a solo voyage in 2014 (aged 37). Kennedy Warnes’, “Like father, like son” is unfortunately apt in this tragic tale.

In modern society where relationships are frequently mediated through virtual reality, or conveyed through idealised social media posts, there is still a place for mucking around in boats, dreaming of voyages, and working alongside a loved one to share a passion (in this case boating). I know I am, in part, who I am, because of a father who nourished a love of boats and boating. I’ll not have the joy of rowing my 92-year-old father out to a boat, but if I do make it to 92 I’ll be sure I’ll celebrate that milestone by going for a row and thanking my father for a lifetime enriched by the sea.

I can’t say I did much in our first joint boat building project. Stormy Petrel looked seaworthy on the lawn but she didn’t float (what can you expect from machinery packing cases?)

A Sunburst sailing dinghy, one of four Dad built with some friends. As kids we handed them some tools and possibly hindered more than helped. My first ‘real’ boat building.

Ursus, 12m launch that consumed countless weekends and holidays over many years (building and boating).

June 2025

Unexpected adventures in the galley: Learning through simple tasks

It’s the third evening on a five-day voyage with a group of year ten boys from a ‘well-to-do’ school. They’d been split into watches and had quickly come to terms with shipboard life. This evening’s watch had assisted a crew member in preparing dinner and were now doing the dishes and tidying up the galley. The dishes were rinsed in salt water and then sent below to be washed, dried, and put away.

I’d been up on deck with other crew members. “I’ll go and check on the dishes team and see how they are getting along”. I went below and found three of the boys in the galley. One was holding a bowl in one hand and was gently rubbing a pot scourer over it, another was looking on, and the third was wiping a ‘cleaned’ bowl with a tea towel. I noticed that there was no hot water nor dishwashing liquid in evidence. When asked where the hot water was, I got a puzzled look. When I inquired about dishwashing liquid, I got an “oh” and the bowl scrubber then attempted to use a handwash dispenser to put soap in the bowl. At which point I had to say, “hold on, how do you wash your dishes at home?” All three responded with “put them in the dishwasher”. “What about things that can’t go in the dishwasher?” I asked. This was met with a blank look – as if to say “are you crazy?” So began a lesson on how to wash dishes, including the need for hot water and dishwashing liquid. The four of us then spent half an hour doing the dishes (including redoing all the ‘cleaned’ dishes that had been done before I arrived). The young lad with the tea towel did admit that it was getting quite dirty from drying the earlier dishes – which is not surprising given it was a pasta meal with mince. It’s not my intention to be disparaging of well-to-do schools. The three young men are not unique within their peer group, nor are they responsible for the fact that their family has the economic capital to remove the ‘burden’ of washing dishes. They’re probably proficient at navigating customs at the airport but using a can opener and washing dishes – what many of us might consider simple life skills – presented a new challenge.

Part of me was saddened that such a simple task would be beyond the life experience of a teenager. I recall many hours standing at the sink, either washing or drying, discussing politics, religion, sport, and economics with my dad. We certainly didn’t agree on everything, but it was a great apprenticeship in critical thinking, and we developed a deep bond from sharing ideas that continued well into adulthood.

As someone invested in youth development, I’ve mulled over how I might engage with young people who are growing in a world vastly different to the one I inhabited. As an educator I’ve valued Glyn Thomas‘s writing on the importance of intentionality; the ability of educators to explain the reasons for an action. Recently I wrote a book chapter with colleagues where we discussed the benefit of ‘burdens’ that provide learning opportunities and foster social interaction (Morten Asfeldt et al.,2025).

Beneficial Burden

Wrestling with the impact of technology in the outdoors is not a new concern. We must be conscious of the inclusion of technology in our practice because, without some scrutiny, inclusion for inclusion’s sake may well mean the loss of other learning opportunities. In the recent chapter we encouraged “outdoor educators to ask not only what is gained by the use of a specific technology but also what is lost”. We proposed the term beneficial burden to represent experiences that appear to be a burden but actually enhance engagement, provide focus, assist in the building of relationships, and provide meaningful life skills.

I will provide a short example to illustrate what this might look like in practice.

Paper verses digital charts

Paper nautical charts are large (110 x 72cm) and require a relatively flat surface to lay them out. To the novice eye they seem to be presented in a foreign language, with various squiggly lines, small numbers, and strange abbreviations. The fact that a minute is a nautical mile (which differs from a land mile) and there are sixty minutes in a degree (as well as an hour) all adds to the strangeness. However, a carefully constructed lesson allows for an explanation of latitude and longitude, the ability to plot a course in true and convert it to a magnetic bearing; in doing so students can learn about the significance of Greenwich, how a sphere is projected onto a flat surface, and the challenge of calculating the vessels actual course over the ground (as opposed to through the water). In short, a skilled educator can incorporate maths, history, physics, English, and geography in a way that is meaningful and lessons learnt can be applied to safely navigating the boat to a desired location.

In contrast a digital chart plotter or tablet, using GPS, displays the boat as an icon on a small screen and the students attention is often on the screen and navigation becomes ‘gamified’ – alter course slightly and watch the icon move in relation to the land. Gone is the need to identify a headland and take a bearing and plot it on a paper chart. Yes, the chart plotter is more accurate but it also ‘compresses’ one’s field of view and hinders situational awareness.

Until recently navigation relied primarily on environmental cues from the land, celestial bodies, and the interpretation of navigational buoys and beacons. The GPS chart plotter potentially de-skills the ‘art’ of navigation and the need for situational awareness. However, there is an argument that developing ‘traditional’ navigational skills, as opposed to a GPS device, is a beneficial burden. It requires the integration of skills, teamwork to take a bearing, record the time, and plot this on a chart. The rise of Indigenous ocean voyaging provides an excellent example of how cultural knowledge is kept alive through navigational practices.

For many of us, the appeal of education outdoors is how we can enhance or engage with people and places, decrease digital distractions, and work towards building a sense of community. In the example provided, I would argue that there are benefits to be gained by intentionally ‘leaning into’ the burden.

Where to from here?

While we cannot alter the technology that students and their families embrace in their ‘everyday worlds’ we can, as intentional educators, think about the possibilities that simple tasks in the outdoors provide to enhance the development of life-skills. The positive aspect of the story that open this blog was that at least 3 young people went away with some new skills, and we got to spend half an hour chatting and building a rapport. This positively changed our relationship over the course of the remainder of the voyage.

It’s important that we are realistic and modest in our claims about what we can realistically achieve in a few days with a group of young people. I believe there is merit in intentionally embedding ‘lofty goals’ (e.g., leadership, teamwork etc.) in practical tasks which relate closely to the realities of everyday life. Intentionality can be exhibited in the decision to forego the using a chart plotter and to use a hand bearing compass, pencil and paper chart. Embedding ‘beneficial burdens’ can form part of an intentional teaching and learning strategy in outdoor education that can enrich the development of demonstrable life skills.

Morten Asfeldt, Bob Henderson, Mike Brown, & Brendon Munge (2025). Technology creep and the beneficial burden. In S. Beames & P. Maher (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Mobile Technology, Social Media and the Outdoors (pp. 358-367). Routledge.

March 2025

Casting off the lines

Late last year I made the decision to go part time at AUT. It was both an easy and difficult decision. Easy because it would mean less commuting and regular time away from home, but difficult in that it marked the end of any further substantial career progression within academia. From a financial perspective reducing my hours was also questionable.

My shift to two days a week at AUT hasn’t meant that I’m working less – I’m juggling four ‘gigs’ and sometimes I’m working far more hours than when I was in full time employment. But what I do have is more flexibility about when I work and the opportunity to invest time/energy into projects that I find rewarding.

I’ve had time to sort out my rather messy library and unpack boxes of books. One of the books that I rediscovered was Paul Heiney’s One Wild Song, an account of his voyage from England to Patagonia and his efforts to come to terms with the loss of his son. Within the first few pages he opines,

isn’t an ocean voyage the greatest of achievements, if an often dangerous and uncertain business? Which way do you turn your head? Forward to the unknown or backwards to the safe? The only answer has to be ever forwards, towards the bow. Backward glances are not the ingredient of true adventures. The start of a new voyage is a time of confused emotions, a tumult of thoughts and feelings every bit as wild as the tumbling of the waves around you. (p.3)

While this year has contained some real voyages under sail, Heiney’s words resonated more at the metaphorical level. As this year draws to a close I find myself reflecting on the decision I made last year. This has certainly been an interesting period of adjustment – an adventurous voyage emotionally and intellectually. It is easy to look back and think about what I forfeited; financially and in terms of a sense of identity associated with being an ‘upwardly mobile’ academic. However, as the year has progressed, I find myself looking forward to 2025, reflecting on what has provided fulfilment, enjoyment and meaning. Mostly these moments involve being with like-minded people, having a laugh and, in some small way helping others to find enjoyment in what they do – whether that be learning to tie a bowline or helping an emerging scholar get published. To paraphrase Paul Heiney, a voyage isn’t necessarily about covering distance, it’s more about gaining understanding. This year has provided opportunities to take stock of what is important. I’m beginning to understand the value of looking towards the bow rather than dwelling in the past. What is known and comfortable doesn’t always equip us to deal with the uncertainties that lie ahead. Casting off the lines, physically and metaphorically isn’t always easy, but it does leave open the potential for new experiences that can be incredibly rewarding.

This photo of Nordwind, winner of the 1939 Fastnet race was taken from Steinlager 2, winner of the 1989 Fastnet. The chances of two champion yachts (winners 50 years apart) being anchored in a bay in the Southern Hemisphere must be one in several million. Great to chat to the crew and hear a little of this vessel’s storied past and future plans.

November 2024

The challenge of words

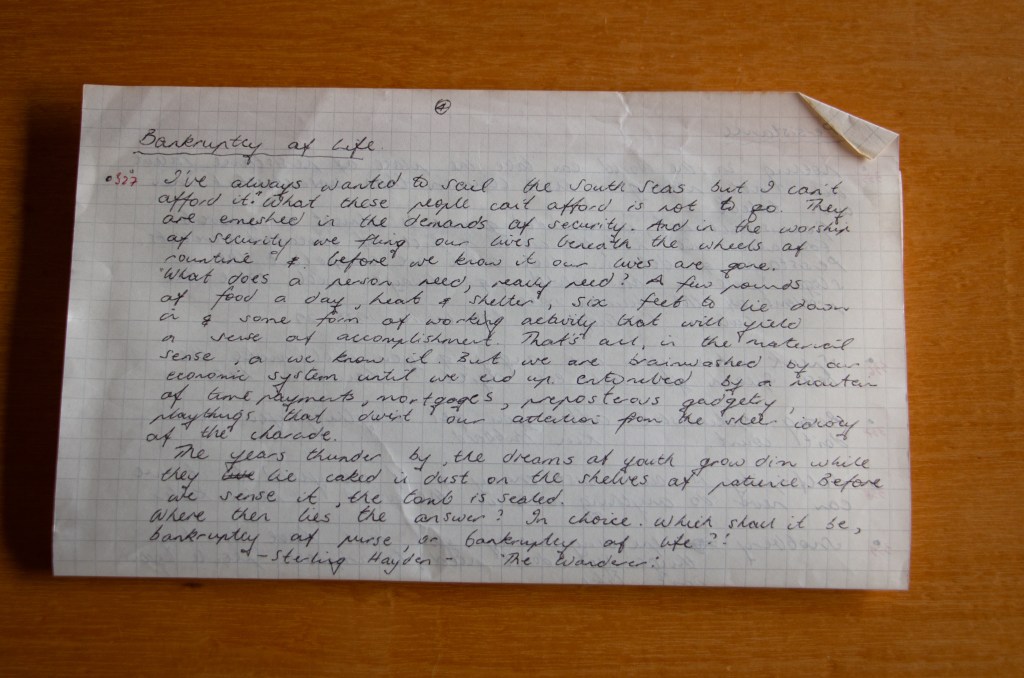

In 1987 I spent a couple of weeks at Outward Bound observing some courses as part of my undergraduate studies. Those three weeks had a profound impact on my subsequent career. It was there that I grasped the educational potential of outdoor experiences. One of the keepsakes from that time was a photocopied version of The Challenge of Words, a collection of readings and inspirational quotes. Four years later I spent a couple of nights dossing on the floor of a friend of a friend in London. There were two other Kiwis in the small flat making arrangements to take up jobs at various UK Outward Bound schools. I was headed to Loch Eil in Scotland and as luck would have it my friend Tony had a copy of The Challenge of Words, as he had recently finished instructing at Anakiwa. Having little money, but ample time, I copied (by hand) 124 readings and quotes from Tony’s book. I’m not sure what my criteria was – perhaps it was because they resonated with where I was at that time in my life – young, enthusiastic, and beginning an exciting adventure. One of the quotes I laboriously wrote out was by someone called Sterling Hayden, whom I had never heard of, but I suspect his reference to sailing, along with my romantic notion that being close to broke was laudable, appealed. Perhaps, in my youthfulness, I rationalized that running low on money meant that I was living a version of Hayden’s ‘rich life’.

My barely legible scrawl

I’ve copied the section below:

I’ve always wanted to sail to the south seas, but I can’t afford it.” What these men can’t afford is not to go. They are enmeshed in the cancerous discipline of “security.” And in the worship of security we fling our lives beneath the wheels of routine – and before we know it our lives are gone.What does a man need – really need? A few pounds of food each day, heat and shelter, six feet to lie down in – and some form of working activity that will yield a sense of accomplishment. That’s all – in the material sense, and we know it. But we are brainwashed by our economic system until we end up in a tomb beneath a pyramid of time payments, mortgages, preposterous gadgetry, playthings that divert our attention for the sheer idiocy of the charade.The years thunder by. The dreams of youth grow dim where they lie caked in dust on the shelves of patience. Before we know it, the tomb is sealed.Where, then, lies the answer? In choice. Which shall it be: bankruptcy of purse or bankruptcy of life? (Sterling Hayden, Wanderer).

I’m not sure how often I used this reading with students in Scotland, or in my time at Outward Bound in New Zealand. While I might not have recited it verbatim it certainly shaped my attitude to what might be termed a ‘sensible career progression’. On three occasions I’ve ended well-paying jobs to pursue things that interested me more, even though the path wasn’t clear or there was a reduction in income.

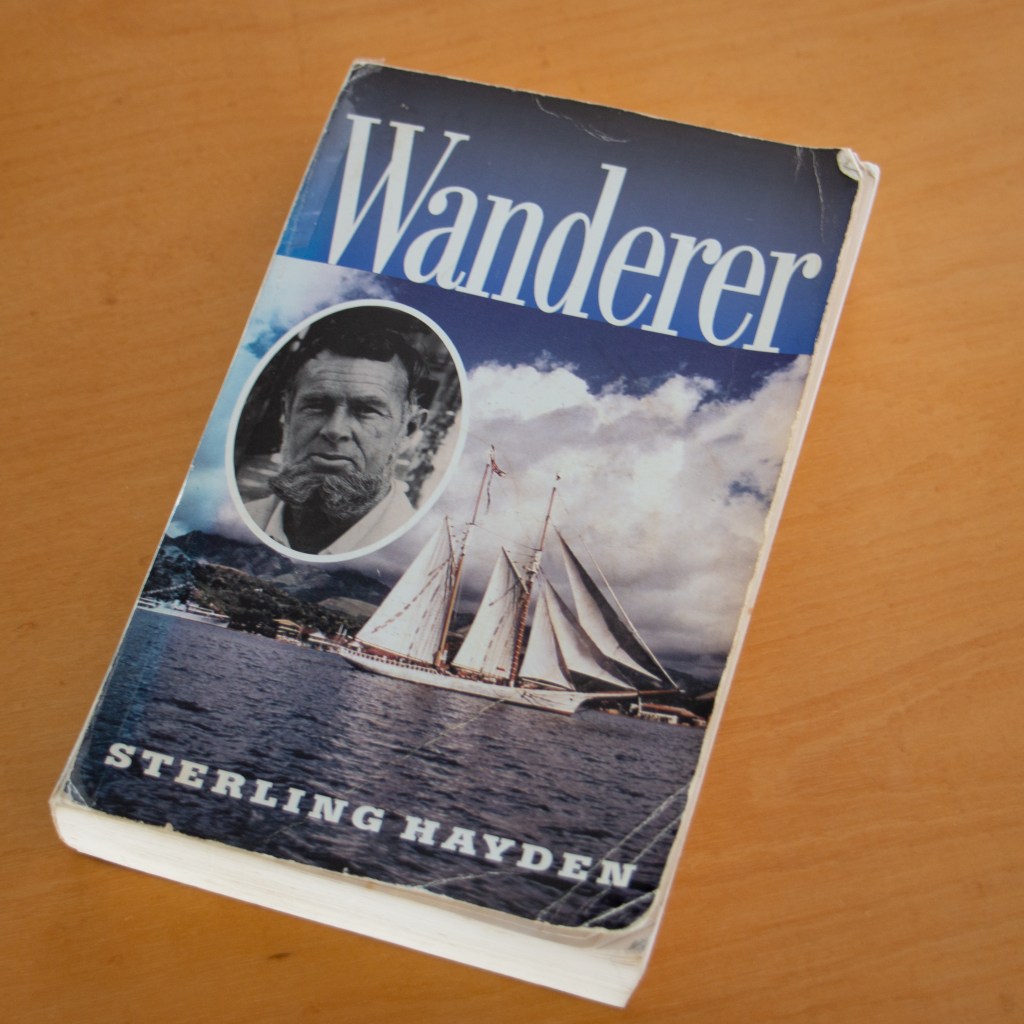

About twenty years after initially writing out this quote I was at a second-hand book fair and came across the book pictured below. I was drawn to the cover (yes, I’m a sucker for a book with a picture of a sailing boat), and for 50c, or maybe $1, it didn’t matter if it wasn’t any good. The cover was held on with sellotape and it had the musty book smell that permeates secondhand bookstores.

Twenty-four pages in and there was the passage that I’d copied out all those years ago. I was now able to place Sterling Hayden and build a picture of his world – sailor, soldier, actor, and author. He saw himself as a sailor or writer rather than an actor, but he is well known for roles in Dr Strangelove, The Godfather, and appearing alongside Bette Davis in The Star. His is an interesting story of ‘accidentally’ ending up in Hollywood but it is clear that his affinity for the sea and sailing took precedence over acting. With hindsight one is tempted to question his advocacy of the merits of financial bankruptcy – his earning potential dwarfed the vast majority of people, for whom the alienating effects of bankruptcy was not just one film role away.

I was recently clearing out some boxes of books and I came across Wanderer and out of it dropped my original handwritten copy of the quote – I must have bookmarked the section when I came across the connection some years ago. Re-reading it brought back memories of when I originally put pen to paper and how the years really have thundered by. I hope the dreams of youth haven’t grown too dim and there’s not a layer of dust on the shelves of patience. I’ve managed to sail some sections of the aforementioned south seas.

Sterling Hayden’s call to live life to the full continues to resonate but I’m not so sure his answer; “in choice”, between “bankruptcy of purse or bankruptcy of life” is the only solution. It’s not as simple as one or the other. A meaningful life is not based on a binary either/or; we are not required to choose one or other of these options. I’m not financially rich, nor am I near financial bankruptcy. I’m not a slave to the economic system that deprives me of meaningful life experiences. My life is enriched by direct engagement with the natural world in the company of valued friends.

I’d suggest that we do have choice but not necessarily in Hayden’s terms. This is well illustrated in the story that Jimmy Carr tells on the Diary of a CEO podcast with Steven Bartlett. Carr recounts the story of a conversation between the authors Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller at a party in the Hamptons. The host is extremely wealthy and has Picasso and Warhol artwork adorning his mansion. Vonnegut turns to Heller and says, “this guy made more money in one day last week than you did out of Catch-22”. Heller replied; “yeah, but I’ve got something he’ll never have – enough”. Perhaps our key choice is to choose when enough is enough? Hayden pointed out that what a person really needs, in the material sense, isn’t that great. The rest is really a diversion.

How much is enough? It’s a deliberate thoughtful choice that we can make. We’re not alone and have some exemplars here in New Zealand. Ranjna Patel, a millionaire businesswoman featured in an RNZ article (14/9/24) defined wealth as, “a roof over your head, food on the table, and a car to get around”. Like Joseph Heller she knows that “you’ve got to know when you’ve got enough”.

So how much is enough? I don’t pretend to know the answer, it’s up to each of us to make a choice, or avoid making a choice and endlessly strive for what is always ‘just around the corner’. One thing is certain – for all of us the years will thunder by.

I’ll admit I’ve not seen any of the movies that Sterling Hayden starred in and I’m not sure that I want to. As a fellow sailor I’m grateful for his words that encourage reflection on what really matters. We might come to different answers but it’s important that we are open to addressing the challenge; “where, then, lies the answer?”

October 2024

Red boats and old boots

Looking out the bus window into the darkness rekindles memories of previous journeys to join a boat. There’re several differences on this trip; I’m not carrying my entire possessions in a backpack, nor am I negotiating London’s underground on my way to connect with a train to an unfamiliar coastal township. It’s over 30 years since I first packed my sailing gear and headed off for a multi-day sail training voyage. Four hours gives me time to reflect on the intervening years. In an odd way it’s a form of circumnavigation, where I’m circling back to where I started. I’m returning to a form of outdoor education that was formative at the genesis of my outdoor career.

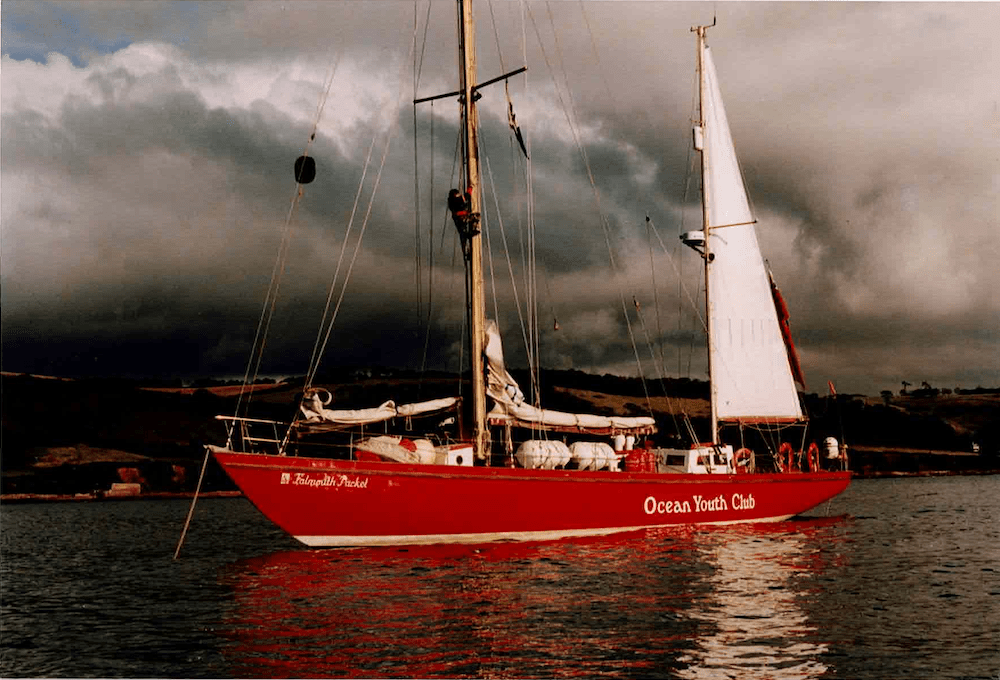

Much has changed in those three decades, not least the emergence of grey hair and ‘laughter lines’. I’d like to think I’m a bit wiser – some days I hope that I am, on others I’m not so sure. There are few touchstones left that connect me to that part of my life as a professional mariner. In the early 1990s I worked as a mate and skipper for the Ocean Youth Club (OYC) in the UK. One of my previous commands is now sitting on the seafloor off the coast of Northern Ireland and I suspect others have been retired or repurposed. I know that a sistership of a vessel I skippered (James Cook), that I served on as first mate (then named John Laing), is now in Australasian waters as Salt Lines.

Falmouth Packet, Cawsand Bay, UK October 1991

I’m travelling from my home in Papamoa to Auckland to join Steinlager 2 for a four-day trip with a group of sixteen 14/5 year old boys. Steinlager 2 and Lion NZ, both owned by the NZ Sailing Trust, are ex Whitbread race yachts campaigned by the late Sir Peter Blake. Steinlager 2, nicknamed ‘Big Red’, won every leg on the 1989/90 round the world race- a feat that was never matched. The boats are not ideal sail training vessels, but they are a privilege to sail. The son of my mum’s work colleague was a crew member on Lion NZ and I remember being shown onboard just after she was launched. I also watched the battle between Steinlager 2 and Fisher and Paykel down the coast, north of Auckland, at the conclusion of the leg from Freemantle to Auckland in early 1990.

Steinlager 2 Kawau Island, NZ 2024

Formative years spent dinghy sailing, helping to build a family boat, and pursuing outdoor activity skills eventually led me to seeking employment with the OYC during my big OE (colloquial term referring to young Kiwis’ overseas experience). This was a baptism by fire where I quickly learnt how to navigate the tidal range in UK waters, deal with the traffic separation scheme in the English Channel, and cope with Royal Marine boarding parties while operating in the Irish Sea – all while learning to manage a crew of 12 trainees and 4 crew members. In two years I managed to trash a set of wet weather gear – there was seldom a day when it wasn’t required – even at the height of a UK summer. The only remaining piece of sailing gear that has survived and is still fully functional are my sea boots. They’ve been as far north as Tobermory on the Isle of Mull and as far south as Cape Horn. They are an odd piece of memorabilia and witness to my development as a sailor and an educator. Perhaps I’m fortunate they can’t talk!

I’m slightly nervous about the next week; after years of working with tertiary aged students, working with adolescent boys will require a different approach. I can vaguely remember both the camaraderie, but also the base level of veiled brutality, of being a teenager at an all-boys school. One thing I can guarantee is that after the first few days the boat will invariably smell like a gym changing room full of body odour and smelly socks – some things don’t change.

The lights of the southern motorway fill the bus and the blackness of the rural landscape is replaced by the glow of streetlights. As we get closer to the city the evening traffic thickens and our pace slows.

I alight and sling my bag over my shoulder and begin my walk towards the harbour. The first time I commenced this ritual I was on my way to another red boat, Falmouth Packet. My parents kept my letters and postcards home (this was pre-internet) and it’s clear from these how much I enjoyed my first foray into sail training – 30 years later I’m still enthusiastic about being at sea and helping to positively shape the lives of young people through direct engagement with the marine environment. Māori refer to the concept of tūrangawaewae, literally knowing where you stand, as a way to think about belonging and identity. Over the years I’ve drawn on the literature from human geography and sociology to explore our relationship to places and how a sense of place or belonging is a fundamental human need. While I am thousands of miles and many years from where I first stood on a sail training boat, I’m looking forward to feeling the deck of another red boat through my faithful seaboots – it’s in this environment that I feel ‘at home’.

Three decades of service

September 2024